The gift databases gave us is this: you can ask a complex SQL question, and the database will magically answer it in the optimal way. In this perfect world, you put data into tables in your data model and things "just work". No management, no overhead, just a beautiful table abstraction and a join machine. Today I want to talk about what we are doing in Floe to help you when the spell breaks.

Asking your database about your database

Our goal for Floe is to create a database that works beautifully and magically in as many cases as possible. From our experience, we know how to handle users that throw us a 5MB text file with a single SQL statement containing 10000 CASE/WHEN branches nested 50 levels deep. We run it to completion: That's table stakes for us (pun intended)!

But we have been around long enough to know that sometimes, no matter how great your SQL engine is, your database needs to answer some questions about itself.

For example:

- "Why is my query slow?"

- "How can I make it faster?"

- "Who are the users making life miserable for everyone?"

- "Which tables take up the most space in my storage and how fast are they growing?"

- "Which data movement jobs consume the most CPU resource in my expensive cloud bill?"

- "What tables get accessed most frequently and by whom?"

- "What code is this view/function actually running? Did I deploy that right?"

We could give you this information in various highly specialised UX experiences you would need to learn. Maybe we could suffer Grafana together? We could send you long, boring log files (classic Java style) with stack traces that you can trawl at your leisure. Perhaps, if we did not think too carefully about things, we could even ask you to collect and send us core dumps that might contain sensitive PII information (like Clickhouse just did: How to opt out of core dump collection).

... Or we could do this right: Proper system views!

A data model for the Database

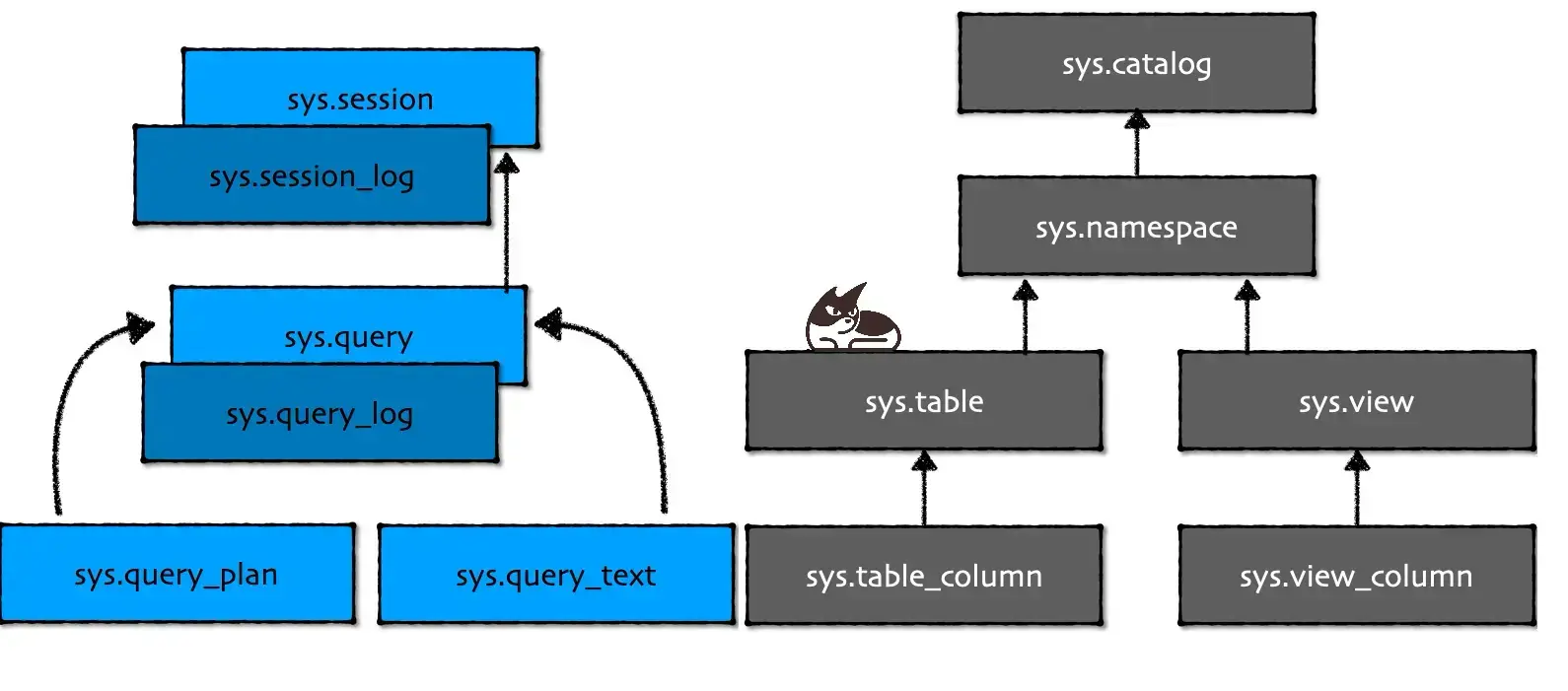

In Floe, every object/class you can talk about in the database is also a system object you can query!

The database contains its own metadata model, in queryable form.

These system objects are stored in as special schema called sys.

Tables, views, functions and friends

Let's warm up with a simple example: Databases contain tables and views. Thus, there is a sys.table and sys.view you can query.

Tables have columns, and columns have statistics (generated by Floecat). That means that we have sys.table_column (views have columns too, but they have slightly different semantics). There is a foreign key from sys.table_column to sys.table - like you would expect. Every row in sys.table_column contains not just the type (keyed to sys.type) of the column and its name, but also the statistic we collect about that column.

For example, you can write a simple query to find columns that take up the most space:

SELECT T.table

, C.table_column

, C.width_bytes_avg * T.row_count AS estimated_size_bytes

FROM sys.table T

JOIN sys.table_column C USING (table_id)

ORDER BY estimated_size_bytes DESC

LIMIT 10

You could ask: "Which tables have a column with the name country where that column has more than two different values":

SELECT table

FROM sys.table T

WHERE EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM sys.table_column C

WHERE T.table_id = C.table_id

AND C.table_column ILIKE '%country%'

AND C.distinct_count > 2)

The beautiful thing about providing SQL access to metadata is this: You might have questions about your data model we did not think about or design a UX to support, and with Floe system views you have the power to answer those questions. In a language you already speak. It also makes automation easier.

We have sys.function where you can find all functions by name and even list their parameters. Including the functions you make yourself with WASM. And we have sys.namespace and sys.catalog that maps to the same concept in Floecat and allow you to query Floecat directly from SQL.

But this is just the easy stuff, allow me to expand the idea.

Sessions, Queries and Plans

When you connect to the Floe database, you establish a session. That session is stored in sys.session and an entry is also written to sys.session_log.

That means you have a full trace, inside the database itself, of who has been connected and when they were there. sys.session_log is immutable, so it also serves as your auditable trace (and you can use our ACL system to control access to it).

A query is a first-class object in Floe, as it probably is in your world. It has a primary key which we call, you guessed it: query_id. We generate query_id when you send the SQL to our engine. Every running query is visible in sys.query and when the query is done running, it moves itself to sys.query_log (notice how it alphabetically sorts nicely in your UX of choice)

You can interact directly with queries – using... queries... For example, imagine that user Big Boss is asking you: "Why is my query running slow?" You can do this:

-- Find the query_id and check what it is doing.

-- Better check that Big Boss isn't just impatient

SELECT query_id -- What ID

, run_ms -- How long?

, state -- What is it doing right now?

FROM sys.query

WHERE username = 'Big Boss'

;

-- What query plan is it running, and where are the rows in the query right now?

EXPLAIN (TEXT) 412354 -- query_id from above

This will give you the actual, running query plan (in the same format that SQL Arena uses). And we will provide warnings in the running query, like this:

WARNING: No Join Key specified in join between tables Foo and Bar

Of course, you can also get the query out in JSON and parse it yourself if that is your thing.

Remember how I told you that all objects in Floe are also system objects? I just talked to you about query plans and showed you the EXPLAIN command. Shouldn't query plans be system objects instead? I am glad you asked: They are! EXPLAIN is just a convenience wrapper.

For example, you can find long-running queries Big Boss was running that have a wild DISTINCT:

SELECT query_plan

, total_ms

, submit_time

FROM sys.query_log

JOIN sys.query_plan USING (query_plain_id)

JOIN sys.query_text USING (query_text_id)

WHERE username = 'Big Boss'

AND total_ms > 30000;

AND query_text ILIKE '%DISTINCT%'

We can use sys.query_stat (which collects statistics about query plans) to find out who likes to cross-join and use DISTINCT, and what that is costing us in terms of compute resources:

SELECT username, SUM(vcpu_ms) AS vcpu_usage

FROM sys.query_log Q

JOIN sys.query_text USING (query_id)

WHERE query_text ILIKE '%DISTINCT%'

/* The query has at least one cross-join that returned a lot of rows */

AND EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM sys.query_stat QS

WHERE QS.query_id = Q.query_id

AND node_type = 'CROSS JOIN'

AND rows_actual > 1000000

)

GROUP BY username

ORDER BY vcpu_usage DESC

Our company Floe isn't just made of SQL lovers; we know that writing SQL queries like the above isn't for everyone. But we are here to be a helpful database, which is why we are giving you additional convenience.

Normal forms and Help for the Join Challenged

The data model of system views is roughly in the third normal form (we refuse to use long character keys). Keys and their foreign key friends are named <table>_id so you can quickly write joins with USING. Naming conventions are consistent, and we have an important document that makes sure we use the right terms across the stack. This should make it easier for you, the user, to consume our system objects and form a mental model of how our database works.

But sometimes, you just want to get some diagnostic data without writing joins and complex queries.

For that, we have special views called sys.diag*. These views, still under specification, provide shortcuts to quick diagnostic of the database for common tasks you perform. You only need the ability to write SELECT * FROM <view> to consume them. And of course, if you don't like that either, we are going to provide a UX as well.

Dear reader, if you made it this far – thanks for sticking with me. Remember that we are actively developing our database right now we would love to hear your feedback and suggestions. We want Floe to be a friendly database that is a delight to run and diagnose – both for experienced power users and new data engineers learning the craft.

The easiest place to reach us at the moment is:

- LinkedIn Page

- Hitting the "Follow Us" button below and signing up for our newsletter

... Still with me? Let us talk about some ugly implementation details.

Choosing Primary Keys

When designing for a distributed system like the cloud, you have to be careful about how you generate keys for tables.

Whenever possible, we are using Snowflake ID for keys. These are 64-bit integers that have some interesting properties in terms of storage layout. For example, they make it much faster to retrieve sys.query_log when you are looking for a specific query_id. It is also much faster to operate on 64-bit values than UUID.

In some cases, we use long hashes (for example, for query_plan_id in sys.query_plan) because that is the natural way to find entries in that cache.

Finally, we also expose the clusters we run in via system objects (via sys.cluster). They will have keys that are UUID because that is what our compute fabric generates.

Compatibility and Protocols

In addition to ADBC, Floe also speaks the PostgreSQL wire protocol.

But before we talk about PostgreSQL – I want to talk about what we mean by a protocol.

The protocol is a contract between a client and the database. Their conversation goes something like this:

- Client: "Knock, Knock"

- Database: "Who goes there? Identify yourself!"

- Client:: "I am Thomas Kejser. Here are my credentials"

- Database:: "Let me check that - OK - what do you want?"

- Client: "Here is some SQL in a wire format you understand, run it!"

- Database:: "OK, here is your result in some serialised format you can read"

- Repeat step 5+6 until satisfied...

Step 6 might include some out-of-band communication like warnings and logging (for example, via the RAISE command in PostgreSQL).

Arrow Flight gives us a very cool way to send data to the client in step 6.

On the surface, this looks straightforward.

Client: "What objects do you have?"

Things get interesting once the client wants to know the metadata of the database.

Traditionally (since the year 1992) this has been done with the ANSI SQL standard for INFORMATION_SCHEMA.

For example, the client could run this SQL statement to find all tables in the database:

SELECT table_catalog, table_schema, table_name

FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.tables

WHERE table_type = 'BASE TABLE'

You can find all schemata (yes, "schemata" is plural of "schema", just like "datum" is singular of "data"):

SELECT schema_name

FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.schemata

Notice how the column containing the name of the schema just changed name? You will also notice the verbosity of these names: slow to type and long to read. Almost every database on the planet supports the INFORMATION_SCHEMA interface, Floe does too.

ADBC to the rescue

ADBC is a new driver standard out to replace ODBC, JDBC and native protocols. With ADBC you need to implement AdbcConnectionGetObjects() and friends to surface metadata to the client driver.

These are clean, easy interfaces for interacting with metadata. We can implement them on top of our sys schema.

Unfortunately, these interfaces are not even close to sufficient for advanced databases, and that is where things get complicated.

There is much more metadata to expose than the standards would have you believe. For example, ADBC is making headway in making statistics generally available with the AdbcConnectionGetStatistics() interface. But that still requires clients to agree to only use that interface.

To truly understand how metadata creates problems for drivers – it is useful to look at PostgreSQL and how this has traditionally been done.

What one might assume about PostgreSQL

To interact with PostgreSQL, most clients go through a library called libpq. This library dates back to the year 1997, it has stood the test of time. It is an extraordinary inefficient library – ripe with copying data around, formatting data types in obscure ways (DECIMAL types stand out as particularly strange), needing byte order swapping and generally giving any driver implementers a headache from the amount of facepalming you do while consuming it.

But if you use Python via psycopg, or if you use ODBC or JDBC against PostgreSQL, chances are that you are talking to libpq behind the scenes. This library is everywhere – you probably have at least one copy on your laptop. Long-lived standards often trump innovation and cool new things.

Libpq tells you what goes on the wire: how to send SQL and how to receive rows. It does not tell you how to talk to the metadata.

In fact, there is no clear definition of what "talking to the metadata" means when you are connected to PostgreSQL or when you are trying to emulate such a connection.

You might think that emulating all the objects in pg_catalog is enough? Wrong!

Let us say you use Datagrip, my preferred IDE for writing queries. The IDE expect a lot of objects, functions and expressions to exist with

the usual, frustrating naming conventions you endure when speaking to a database that has been around for ages (schemaname is a reference to nspname - seriously?).

For example, DataGrip wants these to exist:

- Casting to

oidvia::oidand toregclassvia::regclass age(xid)pg_get_exprarray_lowerandarray_uppergenerate_subscriptsformat_type

This is a relatively small list to support. But that is just the handshake with the database. Try clicking around in the IDE, watch the trace in horror! Even better: Trace Power BI and despair!

There is nowhere you can read what must be implemented to be metadata compatible with PostgreSQL - it simply isn't defined.

There are tests you can run, like the PG core regression tests. But those tests don't tell you what assumptions client tools might make. You have to trace what the tools do on the wire, then surround yourself in tests to make sure you don't regress when a new tool arrives or a new version is made: a constant game of whack a mole!

Wire formats are not the only thing drivers care about - they expect metadata to look at certain way and they expect specific features to be available in the database.

What does this mean for our metadata? It means that while Floe can have its own, rich model of metadata - it must also support older standards when needed. We hope you will find our system views a delight to use - we want them to look and feel great. But we also know that we must emulate the older standards to remain compatible with both modern and old ecosystems.

Summary

We have seen some of the things that follow from the Floe design principle:

- "Every concept you can interact with or observe is also a system object you can query."

This principle drives our metadata design and allow us to support a wide set of drivers and ecosystems. It also provides a powerful diagnostic interface to the database that can be wielded purely from SQL - including by our own developers (yes, we dogfood our metadata).

The exact schema for every system object is still evolving in our code base. One day I want to share a full E/R diagram with you of every single system object and how it relates to the other objects. The database will show its own architecture through its views.

Another design principle follows naturally: namely that every concept can also be controlled with SQL using DDL statements.

But that is a story for another day. You can get that story and many more by hitting that "Follow Us" button below or following us on our LinkedIn Company Page

Happy hacking until we speak again!